TRACEABILITY IN ETHIOPIA, FEEDBACK FROM THE FIELD

As our traceability project in Ethiopia came to an end on April 30, 2024, Walter Matter’s Sustainability Coordinator in Ethiopia, Binyam Temesgen, shared his thoughts from the field about this 18-month initiative dedicated to first mile traceability in the very fragmented Ethiopian coffee supply chain.

Led by Walter Matter and S.A. Bagersh, with the support of the Swiss Agency for Development (SDC), the project took place in the Sidama region to support 3 wet mills in implementing a digital green coffee traceability system.

First-mile traceability in Ethiopia remains a challenge due to the highly fragmented supply chains and elevated number of microholders. How did you find the best approach for this pilot project?

We started by conducting a preliminary survey with all stakeholders in the value chain (farmers, collectors, washing stations) to assess the existing situation and ensure a thorough understanding of existing capacities. The survey allowed us to evaluate expectations and concerns, define priorities, assess available systems, and ultimately design an appropriate traceability strategy as well as an implementation plan with clear objectives, roles and responsibilities.

You were on the front line in leading this project. In your opinion, what were the greatest challenges in its implementation? How did you overcome them?

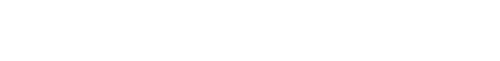

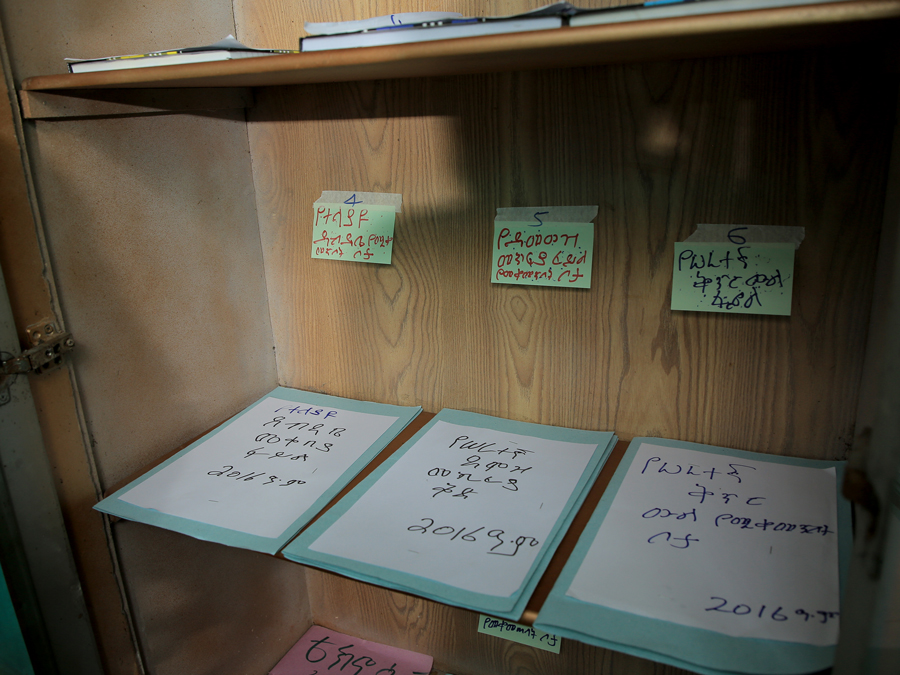

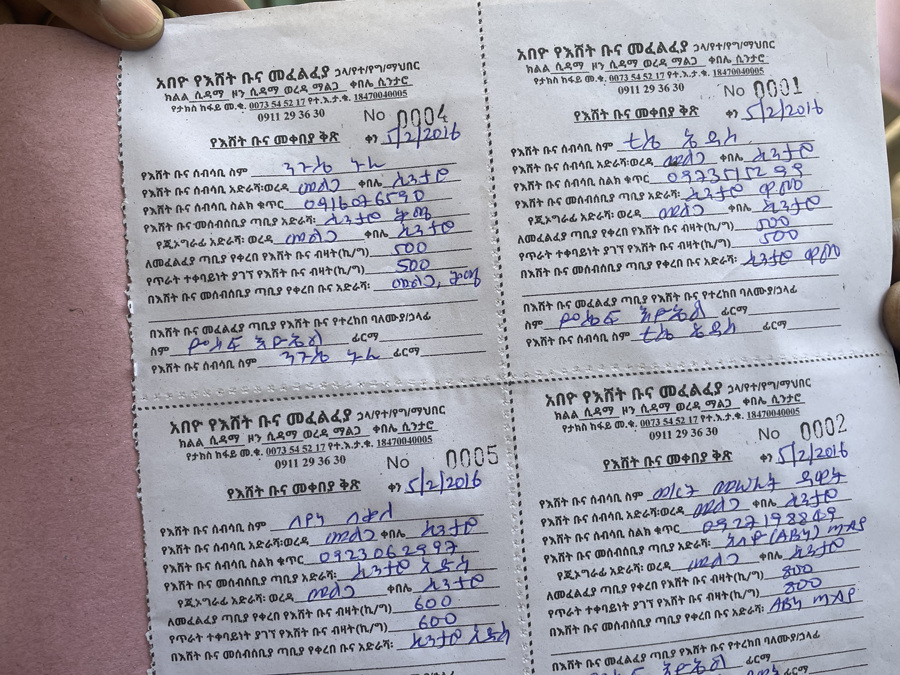

One of the biggest challenges we faced was raising awareness about the importance of traceability, especially at the local level. Many producers, as well as coffee collectors, did not understand why we kept records during purchases; they also feared it would create additional, unpaid work. These combined factors sometimes led them to lose interest in accurately recording data. With the support of washing stations and government authorities, we focused on demonstrating that the record keeping methodology used until then had flaws and posed significant risks to the entire value chain. Illegible handwritten notes, incomplete information, or delays caused by paper-based formats could eventually result in restricted access to the international market.

We also had to deal with unreliable infrastructures, which complicated project implementation. Power, telephone, and internet networks were occasionally unavailable, and roads located in areas with difficult topography, sometimes impassable after heavy rainfall, significantly constrained the day-to-day progress of the project and sometimes limited project beneficiaries’ participation to training sessions.

Finally, many communities outside our target area expressed their desire to be part of the project. It was difficult to decide who to include and, consequently, who to exclude. We had to keep clarifying the project’s scope and reminding everyone that it was a pilot with limited resources.

Despite such challenging conditions, you did manage to deploy a digital traceability system. Which solution was used? How did you deal with the IT illiteracy and the low availability of hardware material such as smartphones or computers?

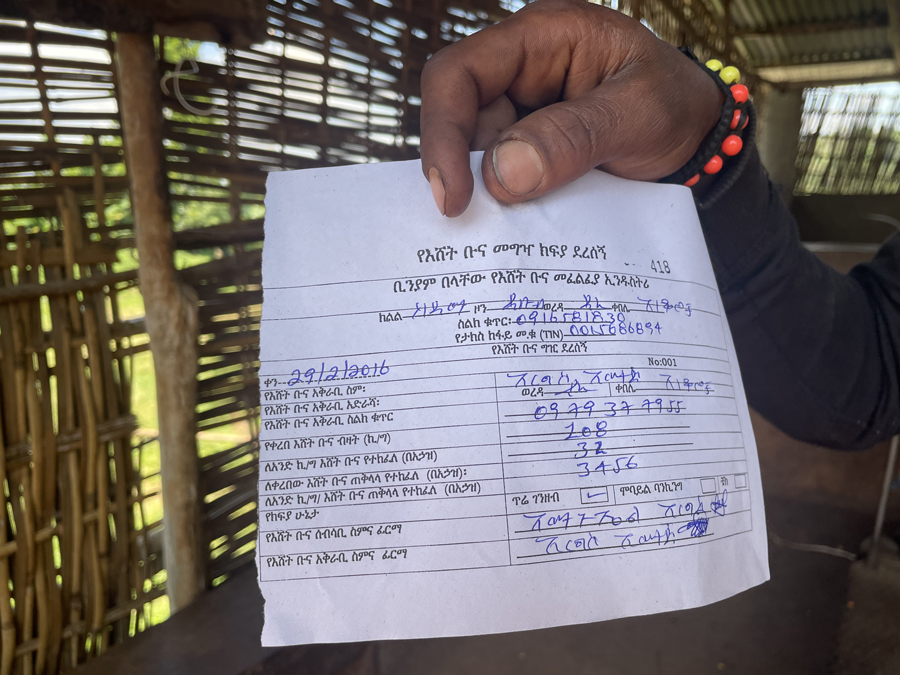

Our traceability model is based on a free open-source solution called KoboToolbox, which allows data collection both online and offline, requiring only a smartphone or a computer. The data can be converted into spreadsheet format, making it easy to share and manage. This model is easily replicable and low cost. The biggest challenge was training participants, whose knowledge of digital tools was limited. Therefore, they were supported throughout the project by our field assistants.

18 months later, what feedback have you received from farmers and wet mills?

At the end of the project, we gathered feedback from all stakeholders, including farmers, collectors, washing stations, and government authorities. A large majority expressed great satisfaction with the support received and the encouraging results achieved in terms of traceability.

Government authorities, for their part, stated that they had learned everything necessary to extend these practices to other washing stations and farming communities.

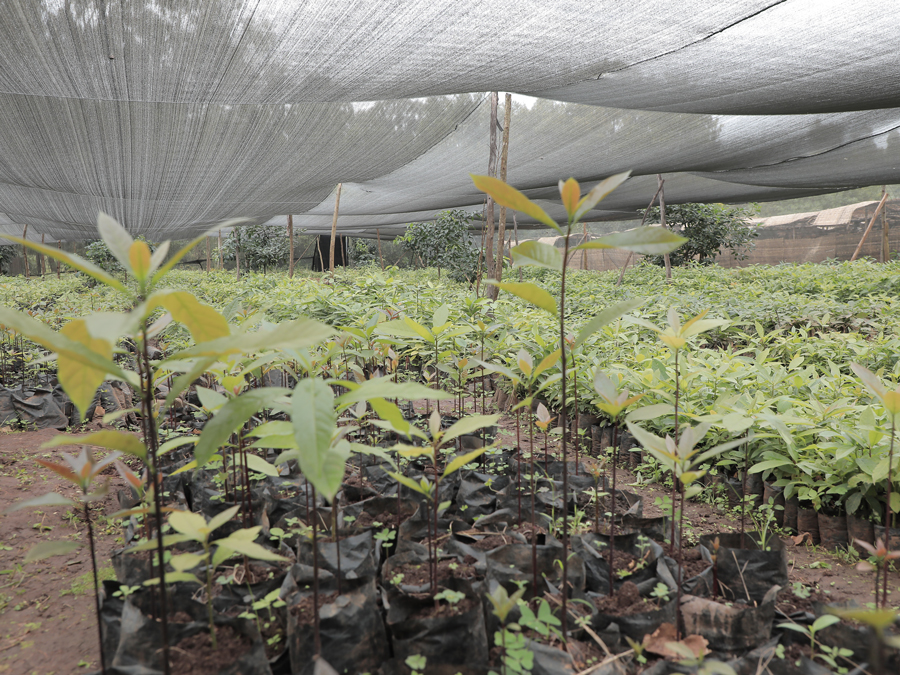

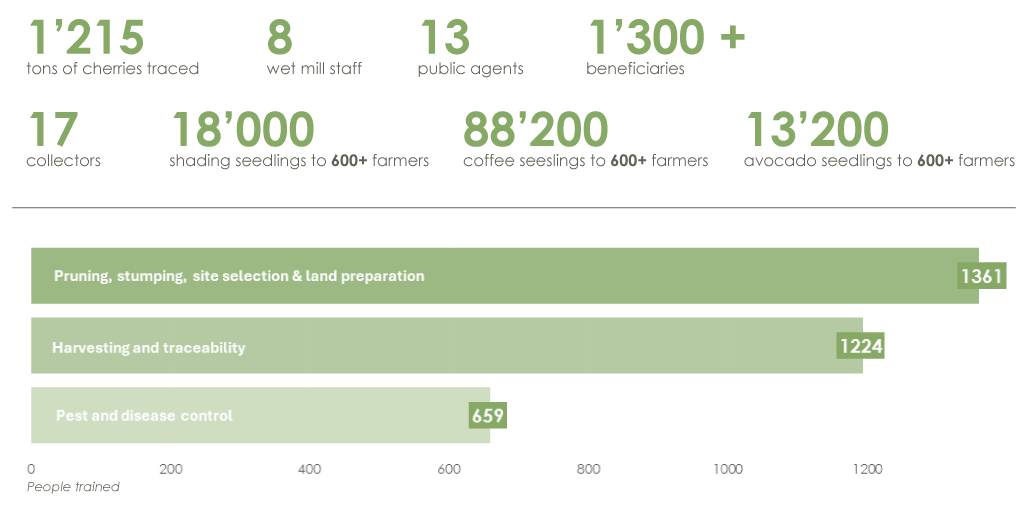

Beyond the implementation of a reliable traceability system, each farmer participating in the project received around 150 coffee seedlings, 30 shade trees to reduce irrigation needs, and 20 avocado trees to diversify their income. Additional training was also provided on pruning, site selection, land preparation, and pest and disease control.

We would like to extend our most sincere thanks to all the participants in this initiative: the farmers who trusted us and participated actively to enable change, the washing stations that played a crucial role in the quality and completeness of data collection, the local authorities whose facilitation role was essential, and finally, the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, for making this pilot project possible in the first place.

RECENT NEWS